The Living Blues

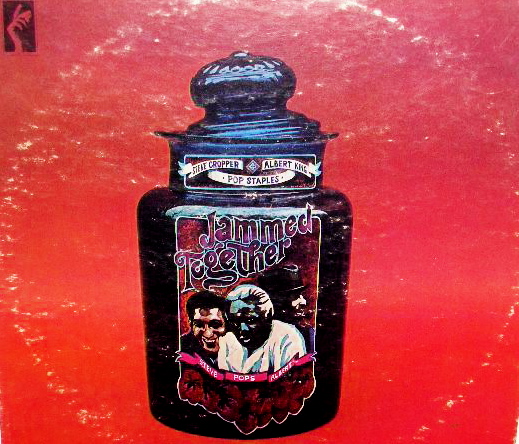

Albert King, Pop Staples & Steve Cropper: Tupelo

taken from the album “Jammed Together” on Stax (1969)

Charlie Musselwhite: Christo Redemptor

taken from the album “Stand Back!” on Vanguard (1966)

There was a time when mixtapes spoke the words that we didn’t know how to. Maybe it was in the eighth grade, and you, lacking the proper tag lines or else not having reached the necessary threshold of drunkenness, couldn’t possibly conjure in your own stoned-out vernacular how you felt about such-and-such dream girl. But you had to tell her somehow. So you spent hours in front of your boom box digging out proper servings “Bonita Applebaum”, “Sexual Healing”, “Brown Eyed Girl”â€â€whatever. The fact that you were jumping more genres, song-to-song, than a David Byrne compilation didn’t matter: What mattered was the message. And how that message was conveyed by the masters; guys who’d been in your selfsame shoes, had a little perspective, and had a few choice lyrics and a nice groove to jam on.

You’d give the girl the tape with a timid grin, and maybe she’d give it a listen and maybe she wouldn’t. And maybe she’d understand the not-so-clandestine message and maybe she wouldn’t. But at least you’d said your piece.

Blues music has always been particulary potent in these contexts. Mainly because, at its core, it is so emotionally evocative. And, not incidentally, because a vast quantity of the stuff was recorded specifically to either woo a girl or to pine her leaving. It comes from an emotional place.

But let’s forget about the girl for a minute. What I’m really getting at is the rawness of the sentiment that is expressed through a plaintive falsetto, or the transcendent power of a repetitive blues riff. In many cases the lyrics themselves are almost arbitrary. (Some of the most moving moments in blues music are in the half-sung, improvised raps in the middle of an otherwise scripted song.) It’s that you can simply feel what is being sung or played or even just rapped about.

So here’s the rub. I was driving up to S.F. about a week and a half agoâ€â€just as the flood waters were rising, and New Orleans was devolving into chaosâ€â€listening to hour after hour of NPR coverage of the horrors going on down there, and I started to feel overwhelmed with all these inexplicable feelings. And I couldn’t make any sense of them. So I turned the radio off somewhere around Fresno. I popped in an old mixtape I had made a few years back and the first song to play is “Tupelo”. And about a minute in, when Pop says “women and children/ screaming and crying, “â€â€man, I just lost it.

Without getting too leaden with the touchy-feely talk, this post is in honor of the folks down there. These tracks resonate very strongly with me right now. Individually and especially together they possess all of the painfully acute resonance of great music that just makes sense given the right context.

The first track is an all-star line-up of Stax vets, Pop Staples (of the more gospel-oriented Staples singers), virtuoso southpaw guitarist Albert King, and Steve Cropper, who, as a founding member of the MG’s, and as a writer/arranger for Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett and Sam & Dave, was instrumental in creating the 60’s southern soul sound. The three of them united on “Jammed Together” (produced by Isaac Hayes) to create an essential late 60’s blues record.

Charlie Musselwhite hailed originally from Missouri, but arrived at legendary bluesman status under the tutelage of the great Sonny Boy Williamson on the Chicago scene in the 60’s. Christo Redemptor (an appropriately Biblical title given the magnitude of the disaster in the Gulf states) is taken from his first release, “Stand Back!”