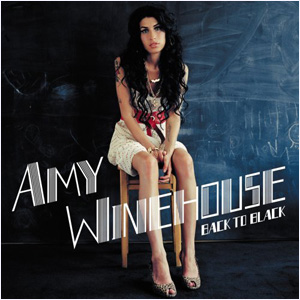

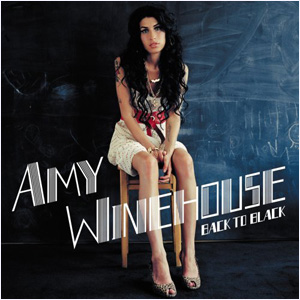

Amy Winehouse: Rehab and Back To Black and He Can Only Hold Her

Taken from the album Back To Black on Interscope (2006)

Broadcasting live from South Africa… Here’s lil’ something something:

Not long ago, soul music fans were hit with a bit of an identity crisis. The kind of dizzying blow that had us perpetually confused about what to buy at the record store. The prickly line of questioning, as we scanned the racks of mediocre R&B, basically ran like this: What to do with the stultified dream of Neo-soul? Who do we turn to with Lauren Hill in absentia? What happens now that D’Angelo’s gone?

Slowly, over time, an answer presented itself: go old school.

The last few years have seen a semi-triumphant re-emergence of throw-back soul. Newer artists, replete with analog mics and calculated band names, trying their hand at a vintage sound, (Sharon Jones and the Dap Kings, Nicole Willis and The Soul Investigators); crate-digger favorites pulling collaborations with slick, beat-minded producers (Spanky Wilson linking up with Quantic); too-smooth studio sessions with the Greats (Al Green, Bettye Swann, Candi Staton) that couldn’t hold a candle to even the more modest work from their respective heydays.

Some, it seems, are trying too hard at an elusive sound. Some have lost their magic touch. Some never had it. Maybe the music doesn’t suit the vocals. The vocals don’t suit the lyrics. The lyrics themselves feel stale. Too hip-hop. Too clean. Too old. Too much effort.

Enter Amy Winehouse with her sophmore album, Back to Black.

That it took a twenty-four year old Jewish girl from north-London to finally make the record that satisfies the proclivity of the recently re-invigorated classic soul music buying public, shouldn’t come as much of a surprise. She’s certainly not the first to tread that road. Joss Stone had a certain appeal, albeit rather white-washed and somewhat lacking in originality. And Alice Russell, who never received a fraction of the praise or notoriety she deserved, did well to work her very contemporary version of classic R&B into a beat-ier, clubbier sound.

But what Winehouse has done is something quite different. She’s made a classically styled R&B record, with real production value, real lyrics, real soul, that doesn’t for a moment sound like something from grandpa’s stash. And even if she nods in all the right directions (there’s no question of the 60’s girl-group influence), the record, as a complete entity, is nothing if not unabashedly contemporary.

Huge props should go to the flawless joint production of Mark Ronson and Salaam Remi, who despite, or perhaps because of, their traditionally hip-hop leanings, have crafted ten songs worth of terse, crisp, pitch perfect orchestration. Just enough strings, without going sappy sweet. Biting horns at all the right intersections. And drums fat enough to move a dancefloor, but that never pander to a generation of beat-greedy rap fans.

Always front and center, though, is Amy Winehouse.

And finally that is what makes this album such a joy to listen to: that the record carries with it the significant artistic identity of the woman herself. For better or worse, Winehouse is a presence. Her young woman’s sexuality, attitude, recklessness, and vocabulary are all on display here. And she doesn’t shy away from much.

The album’s lead off track–carried by easily the catchiest hook I’ve heard in a long while–details Ms. Winehouse’s dogged refusal to undergo rehab for her well-documented alcohol addiction. Her bravado pulses. Similarly, on the cut, “You Know I’m No Good”, she explains, rather unapologetically, her infidilities to a scorned lover. “I told you I was I trouble/ You know I’m no good.” The facts of Amy Winehouse are just that: facts.

The British media has made no bones about exposing Winehouse’s problematic image. From causing public disturbances, to fistfights, to puking onstage, Winehouse may seem hellbent on that type of Billy Holiday-esque self-destruction that makes the admiring fan of her music cringe. But the admiring fan of her music is as likely to appreciate those qualities as despise them. Because Winehouse delivers with the kind of matter-of-factness, with the coarse naivete, with the touching sincerity of a real soul singer.

Amy Winehouse may just be the next in a legacy of R&B artists stretching as far back as the genre itself, to fashion a sound from the painfully palpable transgressions of her private life. But she’s delivered a lot of us who had begun to lose hope in the music, and for that we’re grateful.